Sexual Competition and the Mulatto Man

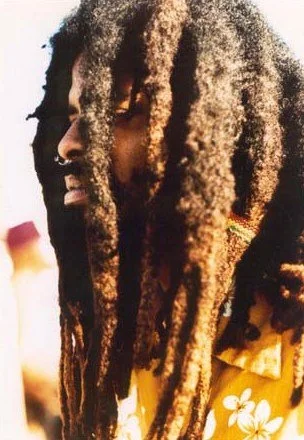

/“Dreadlocked Rasta” is licensed under CC BY SA 3.0

After avoiding her invitation several times prior, I finally agreed to meet with Ms. S, a local music promoter, on Saturday at the Jamaican BrunchFest held at one of Harlem’s most popular Southern restaurants. My wife and I ate there back in August, and the food was so-so, nothing special. I ordered a catfish dinner with black-eyed peas. Unfortunately, my meal was light on catfish—a small overfried strip—and heavy on the peas, which nearly filled the entire plate. When we first sat down, all eyes were on us, and not from the white tourists. Once again, I, the Mulatto man, was singled out for scrutiny by the dark-skinned African American staff and crowd. My dual heritage seemed to unsettle them, and our hostess couldn’t stop asking questions—like whether we lived in the area. I’m convinced she just wanted to satisfy her curiosity about Mulatto speech and mannerisms.

Fast forward to last Saturday. Ms. S contacted me to say that her favorite reggae group would be performing at the brunch from 2 to 5 pm, and she hoped I could attend. Immediately, my apprehension set in. I realized that this particular restaurant would not be rolling out the welcome mat for a Mulatto man, but I decided to go anyway. I arrived around 2:15, met Ms. S, and sat next to her at the bar. A black female bartender with long blond extensions in her hair acknowledged my arrival but didn’t bring me the customary glass of water or a menu that other patrons received without question. I talked with Ms. S for another 20 minutes or so, when a black male bartender, named Delroy, dressed in an ill-fitting navy blue pinstripe suit, mismatched pants, and red sneakers, walked up and slid a laminated menu over to me. No small talk, no welcome to Jamaica Fest, no nothing. A few moments later, the female bartender appeared, unsmiling, holding her portable POS device. I ordered an IPA beer and a plate of truffle fries. Just like my previous encounter with the hostess, this one also asked me to repeat my order as if she couldn’t understand plain English. Maybe if I’d spoken to her in a dialect of Ebonics and ghetto slang, she would have understood. “Is that all you want?” She asked.

“Yes, that’s it,” I said. She poured my beer into a tall glass, occasionally glancing in my direction with a look of disdain on her face. I could tell she didn’t want to serve me, but by law, she had to. The entire time, I smiled at her, just to show I wasn’t going to play her black game of let’s mess with the Mulatto.

I turned around on my barstool, occasionally, to check out the band—a reggae quartet playing covers of Jamaican favorites that were musically tight yet sterile sounding. Don’t get me wrong, I love reggae and ska, but these generic tribute bands that try to mimic the great Bob Marley (who, by the way, was a Mulatto), while pretending to be authentic Rastas with their reggae attire, dreadlocks, phony island slang, and all the other pretentious nonsense, really get on my nerves. Each time I made eye contact with any of the musicians in the band, they looked back with confused expressions, and later with hostile ones. The drummer even avoided me later in the day as he walked through the crowd holding their tip jar. I didn’t know any of these jokers, but clearly, they were offended by my presence.

Around 2:45, Ms. S, who had stepped out to make some phone calls, returned to the bar and introduced me to her friend, Jackie, an attractive light-brown beauty. We immediately hit it off and, as it turned out, shared many interests—food, music, movies, etc. Of course, I’m a married man, probably old enough to be her father, and I had no romantic intentions toward her; however, it was refreshing to talk to a younger woman without having to deal with nonstop questions about my race and nationality, which I seem to get all the time. She had a fabulous figure and wore a light gray off-the-shoulder sweater, which she was constantly adjusting to keep her shapely breasts from popping out. I offered to buy her a drink when, all of a sudden, the black male bartender, Delroy, walked over and interrupted our conversation, asking Jackie if she’d like to try one of his specialty concoctions. “Why not?” she replied. He poured two shots of something that resembled tequila for Jackie and himself. I whispered in Jackie's ear that Delroy had poured her drink in the wrong type of glass, and she started laughing, almost spilling hers on the bar, while Delroy looked on, trying to figure out what was so funny.

Every time Jackie and I started talking about things we liked, especially different kinds of food, Delroy would try to interfere. Finally, he stood in front of Jackie with a sly smirk on his face and said, “It’s almost time for my break.” I figured it was his way of suggesting that Jackie join him privately somewhere in the restaurant.

“Why don’t you go outside?” I said, “It’s nearly 70 degrees today.” (My way of trying to get rid of him!)

“Outside?” he replied, “If I step out there wearing this suit, someone will definitely rob me.” The typical male ploy. He wanted Jackie to think he had money. But to my surprise, she gave him a look of disbelief, rolled her eyes, and said, “Why would anyone want to rob you?” With his ego slightly bruised, Delroy retreated to the other side of the bar, toward all his neglected customers, where he should have been all along instead of bothering us.

It didn’t take long before other black men zeroed in on Jackie and me and made their way over to our side of the bar. I must admit, Jackie was the cream of the crop. When she smiled and laughed, the whole room lit up. These black men weren’t about to let me, a Mulatto man, capture all the glory. They couldn’t stand the sight of Jackie giving me all her attention. They needed to intrude, to find out what I had going on — my game — and what I was saying to impress this young, brown-skinned woman—their sexual preference. The funny thing, though, was that I wasn’t trying to impress her at all. I was only trying to make conversation, and so was she, like two adults who, despite our age difference, had many things in common.

After a tedious second set, the band finally took a break, much to Ms. S's relief, who kept complaining about how loud they were. I was now sitting sideways, facing Jackie, when suddenly I felt someone trying to squeeze between my chair and the person sitting to my left, even though there was plenty of space at the end of the bar. When I turned around, it was none other than the fake rasta bass player scowling at me as if I were his worst enemy. His thick, matted, dried-out hair looked like it hadn’t been washed in years, and smelled like a dead rat covered in coconut oil.

My afternoon at Jamaica Fest ended around 4:30. Delroy, eager to impress Jackie once more, suggested she try another drink called the Continental, along with the usual cranberry and vodka for Ms. S. When he finally set the drinks down, I told him to put them on my tab, and he gave me a quick nod. After saying goodbye to the ladies, with promises to meet again soon, I signaled to the black female bartender for my bill. It wasn’t until I was halfway home that I realized Delroy, that bastard, hadn’t added those last two drinks to my tab. I thought about going back, but that would have been too obvious, too desperate, and definitely embarrassing. I believe he did that on purpose to make me look bad in front of Ms. S and Jackie by charging them for those drinks instead of charging me.

I couldn’t sleep that night thinking about it, so I texted Ms. S on Sunday morning to apologize, but she didn’t reply. What really bothered me, as it turned out, wasn’t so much Ms. S's opinion of me but what Jackie might have thought. Also, I felt like kicking myself for not taking a photo with her, because she was truly a unique, beautiful woman, and I hope we’ll run into each other again one day.

I have no plans to attend another Jamaican Fest at that restaurant unless I receive an invitation from Jackie, which is unlikely. This whole situation was another unfortunate example of the sexual competition between dark-skinned black men and the Mulatto man over the affections of Mulatto or light-skinned black women. I thank God that I’m happily married and no longer have to compete in the dating marketplace.